OFF THE WIRE

'We were handcuffing kids for no reason,' officer Adhyl Polanco testified in the landmark 10-week trial. Photograph: Mario Tama/Getty Images

A federal judge's ruling that the New York City police department has for years turned a blind eye to widespread constitutional rights violations was hardly a surprise to those who have closely tracked the legal challenges to the NYPD's stop-and-frisk regime.

Stop-and-frisk as implemented by the NYPD violates an individual's right to protection under the fourth and 14th amendments of the constitution, judge Shira Scheindlin found in a 195-page ruling. She ordered the appointment of a federal monitor for the nation's largest police force, a measure NYPD commissioner Ray Kelly and New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg have long resisted.

The decision was the result of a landmark two-and-a-half month trial that concluded in May. The federal class action lawsuit, Floyd v City of New York, was filed by four African American men in 2008 who claimed to represent hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers unlawfully stopped by the NYPD. Eight more witnesses, all African American or Latino, also testified to being stopped, and in some cases frisked and searched, unlawfully. Together the plaintiffs described a total of 19 stops. Forty-one police officers also testified, including a recently retired chief of the department, as well as several law enforcement experts. The plaintiffs set out to prove widespread and systemic fourth and 14th constitutional rights violations resulting from the NYPD's stop-and-frisk practices.

Floyd was filed, in part, as a follow-up to a 1999 federal class action suit – Daniels v City of New York – that challenged the NYPD's stop-and-frisk practices. The Daniels settlement required the NYPD to establish a written racial profiling policy in line with the constitution. Additionally, officers who engage in stop-and-frisks were audited, and their supervisors were required to determine whether stops were based on reasonable suspicion. CCR accused the NYPD of failing to comply with the Daniels decree, and filed the Floyd suit in response to the alleged failure.

Scheindlin, who has virtually exclusive authority over the department's most high-profile 4th Amendment and racial profiling cases, presided over both suits. She has issued a number of other rulings against the police department with respect to stop practices in minority communities across the city.

Darius Charney, an attorney for the plaintiffs, said in opening statements that the trial was about more than numbers. "It's about people," he said. The NYPD has "laid siege to black and Latino communities" through "arbitrary, unnecessary and unconstitutional harassment".

Stop-and-frisk has emerged as the premiere law enforcement debate in New York City and is currently playing a central role in the city's ongoing mayoral race. Bloomberg and Kelly have vehemently defended the implementation of stop-and-frisk in the city, arguing that it has played an instrumental role in bringing murder rates to record lows. Critics have countered that the correlation the mayor and the commissioner point to does not prove causation.

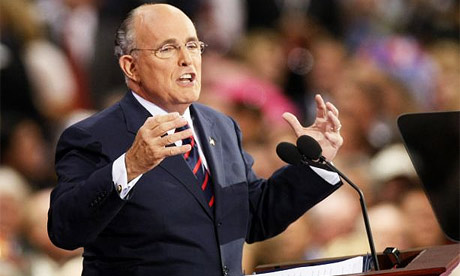

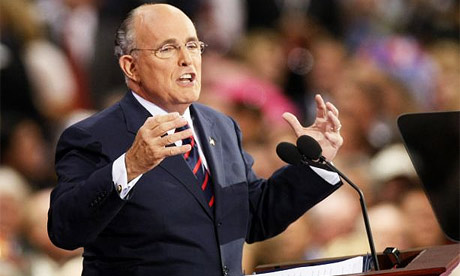

The rise of stop-and-frisk in New York City can be traced back to former New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani, and former NYPD commissioner William Bratton, who embraced a proactive approach to street level policing, informed by computer-based crime data analysis. Though violent crime was dropping nationwide before Giuliani and Bratton's respective appointments, both men were credited with ushering in a new era of safety in New York City. Their law enforcement initiatives, including aggressive stop-and-frisk practices, also garnered praise and support.

The rise of stop-and-frisk can be traced back to former New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani. Photograph: Rick Wilking/Reuters The death of Amadou Diallo, an unarmed African immigrant shot dead by plainclothes officers in the Bronx in 1999, marked a shift in opinion certain NYPD practices, particularly stop-and-frisk and led to sustained protests throughout the city. It also led to the Daniels suit, Floyd's legal predecessor.

The rise of stop-and-frisk can be traced back to former New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani. Photograph: Rick Wilking/Reuters The death of Amadou Diallo, an unarmed African immigrant shot dead by plainclothes officers in the Bronx in 1999, marked a shift in opinion certain NYPD practices, particularly stop-and-frisk and led to sustained protests throughout the city. It also led to the Daniels suit, Floyd's legal predecessor.

With more than 450 exhibits, the Floyd trial generated 8,000 pages of testimony. It also included numerous audio tapes secretly recorded by three NYPD officers in three separate precincts, purporting to capture evidence of supervisors setting quotas for specific numbers of stops, summonses or arrests, and encouraging officers to stop minority youth. Plaintiffs offered surveys compiled by expert law enforcement witnesses intended to prove that under Kelly and Bloomberg, police officers have experienced an increased pressure to make street stops – in order to meet numerical goals – while expectations to adhere to the constitution have faltered.

Lawyers for the plaintiffs in the Floyd suit, meanwhile, maintained that the efficacy of stop-and-frisk has no bearing on the legality of its implementation. The controversy has led to massive protests and an ongoing, divisive political fight. The city council is presently attempting to pass two pieces of legislation that would expand the category of individuals empowered to sue the department for discriminatory practices and establish an inspector general for the NYPD. In the weeks following the trial, the Justice Department threw its support behind a federally appointed monitor for the department, drawing anger from city hall and NYPD supervisors.

The early days of the 10-week trial were often emotional and at times explosive, with young men who have been stopped by the police describing their experiences and dissenting police officers offering up secretly recorded tapes from within their precincts purporting to show the existence of the the NYPD's quota system.

Nicholas Peart, a 24-year-old African American man, struggled for words as he recounted lying face down on the concrete on his 18th birthday, in full public view, as an officer felt his groin and buttocks. He was released without charge. Peart had been visiting his sister at the time and said the stop made him feel as though he did not belong in her neighborhood. Devon Almonor, now 18, who is also African American and the son of a former NYPD cop, said he felt angry and scared when he was stopped, frisked, searched and driven to a police precinct at 13. The officer who stopped Almonor said the boy had been suspiciously looking over his shoulder before he was stopped. The officer admitted to asking the boy why he was "crying like a little girl" as they drove to the precinct. The white officer, who has a son Almonor's age, later testified that his comments may have been inappropriate.

Bronx police officer Pedro Serrano also secretly recorded comments made by supervisors at his precinct. In one recording, Serrano's supervisor, Deputy Inspector Christopher McCormack was heard telling Serrano he needed to stop "the right people, the right time, the right location". When asked what he believed McCormack meant, Serrano told the court: "he meant blacks and Hispanics." Later in the tape McCormack says: "I have no problem telling you this … male blacks. And I told you at roll call, and I have no problem [to] tell you this, male blacks 14 to 21." Serrano claimed his internal attempts to raise concerns about stop-and-frisk and the existence of quotas were met with retaliation, including fellow officers vandalizing his locker with stickers of rats. He choked up on the witness stand as he described his reason for joining the suit. "As a Hispanic living in the Bronx, I have been stopped many times," Serrano said. "I just want to do the right thing." Following his testimony, Serrano was transferred from his precinct without explanation.

Judge Shira Scheindlin handed down a 195-page ruling. Photograph: AP On 1 April, New York state senator Eric Adams, a retired NYPD captain, testified that in a July 2010 meeting he attended with then governor David Patterson, commissioner Kelly stated that stop-and-frisk practices in New York City are designed to "instill fear" in minority communities, particularly among young men. "[Kelly] stated that he targeted and focused on that group because he wanted to instil fear in them that every time that they left their homes they could be targeted by police," Adams testified. "How else would we get rid of guns," Adams said Kelly asked him. Adams told the court he was "amazed" by the commissioner's comment and "told [Kelly] that was illegal." Kelly said in a statement later that he "categorically and totally" denied making the remarks attributed to him by Adams.

Judge Shira Scheindlin handed down a 195-page ruling. Photograph: AP On 1 April, New York state senator Eric Adams, a retired NYPD captain, testified that in a July 2010 meeting he attended with then governor David Patterson, commissioner Kelly stated that stop-and-frisk practices in New York City are designed to "instill fear" in minority communities, particularly among young men. "[Kelly] stated that he targeted and focused on that group because he wanted to instil fear in them that every time that they left their homes they could be targeted by police," Adams testified. "How else would we get rid of guns," Adams said Kelly asked him. Adams told the court he was "amazed" by the commissioner's comment and "told [Kelly] that was illegal." Kelly said in a statement later that he "categorically and totally" denied making the remarks attributed to him by Adams.

Shortly after Adams' testimony, Joseph Esposito, who retired from his role as chief of the department took the stand. Esposito rose to the highest-ranking uniformed officer at the NYPD after 44 years of service. He admitted that street stops had soared on his watch but pointed out a significant decrease in crime rates. When asked if he and Kelly ever discussed "the toll that the policies being challenged here may be having on a generation of black and Latino youth," Esposito said he could not recall. The former police chief also could not recall if he and Kelly had ever discussed the possibility that the department's stop-and-frisk practices could be linked to racial profiling.

Throughout his questioning, Esposito maintained that as long as police officers properly fill out a two-page form when performing stops – made up of a series of checkboxes intended to convey the officer's reasonable suspicion of criminal activity – then racial profiling is impossible. "If it establishes reasonable suspicion, then there is no racial profiling," Esposito testified.

Among the city's star witnesses was officer Kha Dang, who in 2009 was attached to an aggressive plainclothes unit in Brooklyn's 88th precinct. Dang made a total of 127 stops in the third quarter of that year. Though he performed 75 frisks and, on 37 separate occasions, searched inside suspects' clothing or belongings, Dang wrote just one summons and only found contraband once. He never recovered any weapons and he only stopped people of color. He never stopped a white person.

The testimony of the plaintiffs' statistical expert was central to their 4th amendment case. Drawing on NYPD stop data from 2004 to 2012, Columbia professor Jeffrey Fagan testified that "racial composition of [a] neighborhood is a statistically significant predictor of stop rates." Fagan also found that African Americans and Latinos are 14% more likely to have force used against them in stops than whites. Fagan's testimony was among the lengthiest in the trial and drew heavy criticism from the city's attorneys, who have long challenged his methodology.

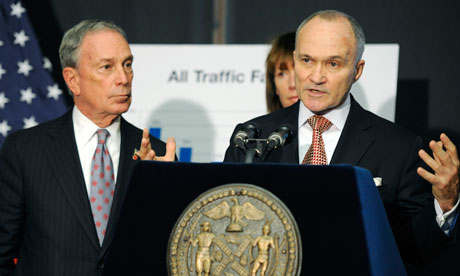

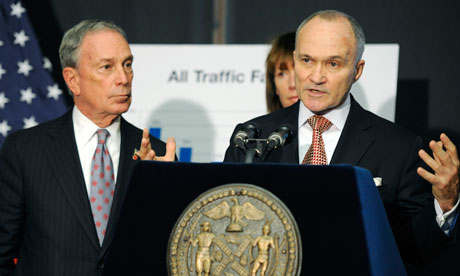

Michael Bloomberg and NYPD commissioner Ray Kelly have stood by the controversial policy. Photograph: Henny Ray Abrams/AP While neither Kelly nor Bloomberg testified to defend their shared law enforcement legacy, both leaned on the media and public comments to weigh in on the trial. In a speech at police headquarters in early May, as the trial entered its closing phases, Bloomberg declared the NYPD was "under attack" and mounted an impassioned 22-minute defense of the department, rejecting the central claims in the case. The following night, Kelly told ABC News the NYPD is run like a major business and said African Americans were not stopped as much as they might be. A month earlier Kelly appeared on a local NY1 news show, Road to City Hall, and attempted to discredit Scheindlin. "In my view, the judge is very much in their corner and has been all along throughout her career," he said. In the final week of testimony, the mayor's office leaked an internal report to the New York Daily News purporting to show that judge Scheindlin is "biased against law enforcement." Scheindlin called the report "completely misleading." The New York County Lawyers' Association wrote a letter to the Daily News to protest the article. During a June radio interview Bloomberg argued that, based on witness and murder victim descriptions "we disproportionately stop whites too much and minorities too little." The mayor also claimed that "nobody racially profiles."

Michael Bloomberg and NYPD commissioner Ray Kelly have stood by the controversial policy. Photograph: Henny Ray Abrams/AP While neither Kelly nor Bloomberg testified to defend their shared law enforcement legacy, both leaned on the media and public comments to weigh in on the trial. In a speech at police headquarters in early May, as the trial entered its closing phases, Bloomberg declared the NYPD was "under attack" and mounted an impassioned 22-minute defense of the department, rejecting the central claims in the case. The following night, Kelly told ABC News the NYPD is run like a major business and said African Americans were not stopped as much as they might be. A month earlier Kelly appeared on a local NY1 news show, Road to City Hall, and attempted to discredit Scheindlin. "In my view, the judge is very much in their corner and has been all along throughout her career," he said. In the final week of testimony, the mayor's office leaked an internal report to the New York Daily News purporting to show that judge Scheindlin is "biased against law enforcement." Scheindlin called the report "completely misleading." The New York County Lawyers' Association wrote a letter to the Daily News to protest the article. During a June radio interview Bloomberg argued that, based on witness and murder victim descriptions "we disproportionately stop whites too much and minorities too little." The mayor also claimed that "nobody racially profiles."

In closing arguments, attorneys for the plaintiffs proposed a number of solutions to insure NYPD street stops are constitutional, including revising forms officers fill out when stopping people to include a narrative component requiring them to articulate the reasonable suspicion behind their stops. The plaintiffs also called for the establishment of a court-appointed monitor. The city's attorneys, meanwhile, dismissed allegations of an NYPD quota system as a "sideshow" and said the plaintiffs "failed to show a single constitutional violation, much less a widespread pattern or practice." Attorney Heidi Grossman said, "The alleged complaints of racial profiling are more fiction than reality."

Scheindlin challenged the city on the the number of stops resulting in arrests, summonses or weapons seizures, its so-called "hit rate". According to department data, out of 4.3m stops conducted between 2004 and 2012, fewer than 1% uncovered weapons and 0.14% led to a gun. "What troubles me is the suspicion seems to be wrong 90% of the time," Scheindlin said. "What can I infer from that?"

"We don't believe [the court] should be concerned about the hit rate," Grossman said, arguing a stop that did not result in a ticket or arrest could still prevent a crime.

Stop-and-frisk as implemented by the NYPD violates an individual's right to protection under the fourth and 14th amendments of the constitution, judge Shira Scheindlin found in a 195-page ruling. She ordered the appointment of a federal monitor for the nation's largest police force, a measure NYPD commissioner Ray Kelly and New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg have long resisted.

The decision was the result of a landmark two-and-a-half month trial that concluded in May. The federal class action lawsuit, Floyd v City of New York, was filed by four African American men in 2008 who claimed to represent hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers unlawfully stopped by the NYPD. Eight more witnesses, all African American or Latino, also testified to being stopped, and in some cases frisked and searched, unlawfully. Together the plaintiffs described a total of 19 stops. Forty-one police officers also testified, including a recently retired chief of the department, as well as several law enforcement experts. The plaintiffs set out to prove widespread and systemic fourth and 14th constitutional rights violations resulting from the NYPD's stop-and-frisk practices.

Floyd was filed, in part, as a follow-up to a 1999 federal class action suit – Daniels v City of New York – that challenged the NYPD's stop-and-frisk practices. The Daniels settlement required the NYPD to establish a written racial profiling policy in line with the constitution. Additionally, officers who engage in stop-and-frisks were audited, and their supervisors were required to determine whether stops were based on reasonable suspicion. CCR accused the NYPD of failing to comply with the Daniels decree, and filed the Floyd suit in response to the alleged failure.

Scheindlin, who has virtually exclusive authority over the department's most high-profile 4th Amendment and racial profiling cases, presided over both suits. She has issued a number of other rulings against the police department with respect to stop practices in minority communities across the city.

Five million people have been stopped and frisked in last decade

Approximately 5 million people have been stopped by the NYPD over the last decade. The vast majority have been African American or Latino and roughly nine out of 10 have walked away without an arrest or a ticket. By law, a police officer must have reasonable suspicion that a crime is about to occur or has occurred in order to make a stop.Darius Charney, an attorney for the plaintiffs, said in opening statements that the trial was about more than numbers. "It's about people," he said. The NYPD has "laid siege to black and Latino communities" through "arbitrary, unnecessary and unconstitutional harassment".

Stop-and-frisk has emerged as the premiere law enforcement debate in New York City and is currently playing a central role in the city's ongoing mayoral race. Bloomberg and Kelly have vehemently defended the implementation of stop-and-frisk in the city, arguing that it has played an instrumental role in bringing murder rates to record lows. Critics have countered that the correlation the mayor and the commissioner point to does not prove causation.

The rise of stop-and-frisk in New York City can be traced back to former New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani, and former NYPD commissioner William Bratton, who embraced a proactive approach to street level policing, informed by computer-based crime data analysis. Though violent crime was dropping nationwide before Giuliani and Bratton's respective appointments, both men were credited with ushering in a new era of safety in New York City. Their law enforcement initiatives, including aggressive stop-and-frisk practices, also garnered praise and support.

The rise of stop-and-frisk can be traced back to former New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani. Photograph: Rick Wilking/Reuters The death of Amadou Diallo, an unarmed African immigrant shot dead by plainclothes officers in the Bronx in 1999, marked a shift in opinion certain NYPD practices, particularly stop-and-frisk and led to sustained protests throughout the city. It also led to the Daniels suit, Floyd's legal predecessor.

The rise of stop-and-frisk can be traced back to former New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani. Photograph: Rick Wilking/Reuters The death of Amadou Diallo, an unarmed African immigrant shot dead by plainclothes officers in the Bronx in 1999, marked a shift in opinion certain NYPD practices, particularly stop-and-frisk and led to sustained protests throughout the city. It also led to the Daniels suit, Floyd's legal predecessor.With more than 450 exhibits, the Floyd trial generated 8,000 pages of testimony. It also included numerous audio tapes secretly recorded by three NYPD officers in three separate precincts, purporting to capture evidence of supervisors setting quotas for specific numbers of stops, summonses or arrests, and encouraging officers to stop minority youth. Plaintiffs offered surveys compiled by expert law enforcement witnesses intended to prove that under Kelly and Bloomberg, police officers have experienced an increased pressure to make street stops – in order to meet numerical goals – while expectations to adhere to the constitution have faltered.

Lawyers for the plaintiffs in the Floyd suit, meanwhile, maintained that the efficacy of stop-and-frisk has no bearing on the legality of its implementation. The controversy has led to massive protests and an ongoing, divisive political fight. The city council is presently attempting to pass two pieces of legislation that would expand the category of individuals empowered to sue the department for discriminatory practices and establish an inspector general for the NYPD. In the weeks following the trial, the Justice Department threw its support behind a federally appointed monitor for the department, drawing anger from city hall and NYPD supervisors.

The early days of the 10-week trial were often emotional and at times explosive, with young men who have been stopped by the police describing their experiences and dissenting police officers offering up secretly recorded tapes from within their precincts purporting to show the existence of the the NYPD's quota system.

Nicholas Peart, a 24-year-old African American man, struggled for words as he recounted lying face down on the concrete on his 18th birthday, in full public view, as an officer felt his groin and buttocks. He was released without charge. Peart had been visiting his sister at the time and said the stop made him feel as though he did not belong in her neighborhood. Devon Almonor, now 18, who is also African American and the son of a former NYPD cop, said he felt angry and scared when he was stopped, frisked, searched and driven to a police precinct at 13. The officer who stopped Almonor said the boy had been suspiciously looking over his shoulder before he was stopped. The officer admitted to asking the boy why he was "crying like a little girl" as they drove to the precinct. The white officer, who has a son Almonor's age, later testified that his comments may have been inappropriate.

'What goes on out there'

Officer Adhyl Polanco testified that "there's a difference between" the department's policies on paper and "what goes on out there", on the city's streets. Officers in his Bronx precinct were expected to issue 20 summons and make one arrest per month, Polanco testified. If they did not they would risk denied vacation, being separated from longtime partners, undesirable assignments and other consequences. "We were handcuffing kids for no reason," Polanco said. Claiming he was increasingly disturbed by what he was witnessing in his precinct, Polcanco began secretly recording his roll call meetings. In one recording played for the court, a man Polanco claimed was a NYPD captain told officers: "the summons is a money–generating machine for the city."Bronx police officer Pedro Serrano also secretly recorded comments made by supervisors at his precinct. In one recording, Serrano's supervisor, Deputy Inspector Christopher McCormack was heard telling Serrano he needed to stop "the right people, the right time, the right location". When asked what he believed McCormack meant, Serrano told the court: "he meant blacks and Hispanics." Later in the tape McCormack says: "I have no problem telling you this … male blacks. And I told you at roll call, and I have no problem [to] tell you this, male blacks 14 to 21." Serrano claimed his internal attempts to raise concerns about stop-and-frisk and the existence of quotas were met with retaliation, including fellow officers vandalizing his locker with stickers of rats. He choked up on the witness stand as he described his reason for joining the suit. "As a Hispanic living in the Bronx, I have been stopped many times," Serrano said. "I just want to do the right thing." Following his testimony, Serrano was transferred from his precinct without explanation.

Judge Shira Scheindlin handed down a 195-page ruling. Photograph: AP On 1 April, New York state senator Eric Adams, a retired NYPD captain, testified that in a July 2010 meeting he attended with then governor David Patterson, commissioner Kelly stated that stop-and-frisk practices in New York City are designed to "instill fear" in minority communities, particularly among young men. "[Kelly] stated that he targeted and focused on that group because he wanted to instil fear in them that every time that they left their homes they could be targeted by police," Adams testified. "How else would we get rid of guns," Adams said Kelly asked him. Adams told the court he was "amazed" by the commissioner's comment and "told [Kelly] that was illegal." Kelly said in a statement later that he "categorically and totally" denied making the remarks attributed to him by Adams.

Judge Shira Scheindlin handed down a 195-page ruling. Photograph: AP On 1 April, New York state senator Eric Adams, a retired NYPD captain, testified that in a July 2010 meeting he attended with then governor David Patterson, commissioner Kelly stated that stop-and-frisk practices in New York City are designed to "instill fear" in minority communities, particularly among young men. "[Kelly] stated that he targeted and focused on that group because he wanted to instil fear in them that every time that they left their homes they could be targeted by police," Adams testified. "How else would we get rid of guns," Adams said Kelly asked him. Adams told the court he was "amazed" by the commissioner's comment and "told [Kelly] that was illegal." Kelly said in a statement later that he "categorically and totally" denied making the remarks attributed to him by Adams.Shortly after Adams' testimony, Joseph Esposito, who retired from his role as chief of the department took the stand. Esposito rose to the highest-ranking uniformed officer at the NYPD after 44 years of service. He admitted that street stops had soared on his watch but pointed out a significant decrease in crime rates. When asked if he and Kelly ever discussed "the toll that the policies being challenged here may be having on a generation of black and Latino youth," Esposito said he could not recall. The former police chief also could not recall if he and Kelly had ever discussed the possibility that the department's stop-and-frisk practices could be linked to racial profiling.

Throughout his questioning, Esposito maintained that as long as police officers properly fill out a two-page form when performing stops – made up of a series of checkboxes intended to convey the officer's reasonable suspicion of criminal activity – then racial profiling is impossible. "If it establishes reasonable suspicion, then there is no racial profiling," Esposito testified.

Among the city's star witnesses was officer Kha Dang, who in 2009 was attached to an aggressive plainclothes unit in Brooklyn's 88th precinct. Dang made a total of 127 stops in the third quarter of that year. Though he performed 75 frisks and, on 37 separate occasions, searched inside suspects' clothing or belongings, Dang wrote just one summons and only found contraband once. He never recovered any weapons and he only stopped people of color. He never stopped a white person.

'More fiction than reality'

Dang told the court his stops were motivated by by what he called "weird behavior" or "furtive movement." The latter phrase came up repeatedly throughout the course of the trial. Along with "high crime area", furtive movement is the justification NYPD officers most frequently check off on departmental stop forms known as UF250s. Critics say it's a dangerously vague term that allows officers overly broad discretion in conducting stops. Dang provided the court with examples of furtive movement which included: "hanging out in front of a building, sitting on benches or something like that" and "standing near benches or trash cans."The testimony of the plaintiffs' statistical expert was central to their 4th amendment case. Drawing on NYPD stop data from 2004 to 2012, Columbia professor Jeffrey Fagan testified that "racial composition of [a] neighborhood is a statistically significant predictor of stop rates." Fagan also found that African Americans and Latinos are 14% more likely to have force used against them in stops than whites. Fagan's testimony was among the lengthiest in the trial and drew heavy criticism from the city's attorneys, who have long challenged his methodology.

Michael Bloomberg and NYPD commissioner Ray Kelly have stood by the controversial policy. Photograph: Henny Ray Abrams/AP While neither Kelly nor Bloomberg testified to defend their shared law enforcement legacy, both leaned on the media and public comments to weigh in on the trial. In a speech at police headquarters in early May, as the trial entered its closing phases, Bloomberg declared the NYPD was "under attack" and mounted an impassioned 22-minute defense of the department, rejecting the central claims in the case. The following night, Kelly told ABC News the NYPD is run like a major business and said African Americans were not stopped as much as they might be. A month earlier Kelly appeared on a local NY1 news show, Road to City Hall, and attempted to discredit Scheindlin. "In my view, the judge is very much in their corner and has been all along throughout her career," he said. In the final week of testimony, the mayor's office leaked an internal report to the New York Daily News purporting to show that judge Scheindlin is "biased against law enforcement." Scheindlin called the report "completely misleading." The New York County Lawyers' Association wrote a letter to the Daily News to protest the article. During a June radio interview Bloomberg argued that, based on witness and murder victim descriptions "we disproportionately stop whites too much and minorities too little." The mayor also claimed that "nobody racially profiles."

Michael Bloomberg and NYPD commissioner Ray Kelly have stood by the controversial policy. Photograph: Henny Ray Abrams/AP While neither Kelly nor Bloomberg testified to defend their shared law enforcement legacy, both leaned on the media and public comments to weigh in on the trial. In a speech at police headquarters in early May, as the trial entered its closing phases, Bloomberg declared the NYPD was "under attack" and mounted an impassioned 22-minute defense of the department, rejecting the central claims in the case. The following night, Kelly told ABC News the NYPD is run like a major business and said African Americans were not stopped as much as they might be. A month earlier Kelly appeared on a local NY1 news show, Road to City Hall, and attempted to discredit Scheindlin. "In my view, the judge is very much in their corner and has been all along throughout her career," he said. In the final week of testimony, the mayor's office leaked an internal report to the New York Daily News purporting to show that judge Scheindlin is "biased against law enforcement." Scheindlin called the report "completely misleading." The New York County Lawyers' Association wrote a letter to the Daily News to protest the article. During a June radio interview Bloomberg argued that, based on witness and murder victim descriptions "we disproportionately stop whites too much and minorities too little." The mayor also claimed that "nobody racially profiles."In closing arguments, attorneys for the plaintiffs proposed a number of solutions to insure NYPD street stops are constitutional, including revising forms officers fill out when stopping people to include a narrative component requiring them to articulate the reasonable suspicion behind their stops. The plaintiffs also called for the establishment of a court-appointed monitor. The city's attorneys, meanwhile, dismissed allegations of an NYPD quota system as a "sideshow" and said the plaintiffs "failed to show a single constitutional violation, much less a widespread pattern or practice." Attorney Heidi Grossman said, "The alleged complaints of racial profiling are more fiction than reality."

Scheindlin challenged the city on the the number of stops resulting in arrests, summonses or weapons seizures, its so-called "hit rate". According to department data, out of 4.3m stops conducted between 2004 and 2012, fewer than 1% uncovered weapons and 0.14% led to a gun. "What troubles me is the suspicion seems to be wrong 90% of the time," Scheindlin said. "What can I infer from that?"

"We don't believe [the court] should be concerned about the hit rate," Grossman said, arguing a stop that did not result in a ticket or arrest could still prevent a crime.

0 comments:

Post a Comment